Milkweed is a gorgeous flower that comes in many stunning varieties and makes a beautiful addition to any garden, but there’s more to it than just a pretty face! Milkweed is also integral to the life cycle of the monarch butterfly, and planting it in the garden can help save these beneficial critters whose numbers are dwindling.

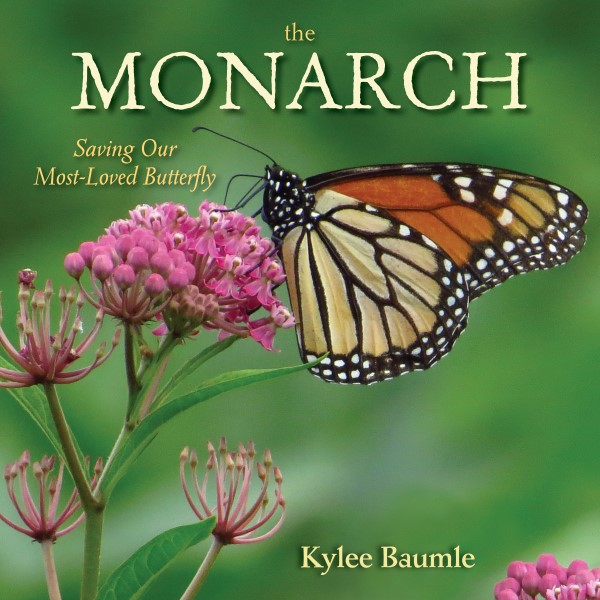

Garden photographer and writer Kylee Baumle is here to give us the facts on growing milkweed to help protect our flitting friends. Kylee is the author of The Monarch: Saving Our Most-Loved Butterfly, and her rural Ohio garden is a Certified Monarch Waystation (#948) since 2006, a Certified Wildlife Habitat, and is registered with Pollinator Partnership as part of The Million Pollinator Garden Challenge, so she knows a thing or two.

Kylee’s book is all about the decrease in monarch populations, what we can do to help, and why it matters. She joins us today to answer a burning question about milkweed.

What’s So Special About Milkweed?

By Kylee Baumle

Every species of butterfly has specific host plants on which they raise their young. Many have a number of acceptable host plants, but the monarch utilizes only one group of plants: milkweeds. Part of the reason is that these plants contain a characteristic milky latex sap, giving them their common name.

This sap contains toxic compounds known as cardenolides which, when consumed by the monarch caterpillars, renders them toxic to some would-be predators. This protection is carried over in the adult butterfly; birds often discover them to be distasteful to the point of making the bird ill. The bird is then conditioned to avoid this brightly-marked butterfly so as to not experience that again!

Strange but True

Though milkweed provides nourishment for monarch caterpillars, the latex sap inside the plants that helps protect the caterpillars from predators can sometimes spell their death. One study has shown that of the monarch caterpillars that did not survive to adulthood, nearly 30% perished due to the sticky sap gumming up the mandibles of the caterpillar, preventing it from eating. Older caterpillars learn to chew through the large vein of a leaf, effectively stopping the flow of latex to the leaf, thus allowing the caterpillar to eat safely.

What kind of milkweed should I grow?

As mentioned previously, it is recommended that gardeners plant milkweeds that are native to their region. But there are a few types that are suitable over a wide area of the monarch’s range.

Common Milkweed (Asclepias syriaca)

- Light: Full sun

- Water: Average

- USDA Zone: 3-9

- Size: 3-5 feet tall, sometimes taller

Swamp Milkweed (Asclepias incarnata)

- Light: Full sun to part shade

- Water: Average to wet

- USDA Zone: 3-6

- Size: 3-5 feet tall

Butterfly Weed (Asclepias tuberosa)

- Light: Full sun

- Water: Dry to moist, drought tolerant

- USDA Zone: 3-9

- Size: 1-3 feet tall

Poke Milkweed (Asclepias exaltata)

- Light: Full shade to part shade

- Water: Average to dry

- USDA Zone: 4-7

- Size: 2-6 feet tall

Purple Milkweed (Asclepias purpurascens)

- Light: Full sun

- Water: Average to dry

- USDA Zone: 3-8

- Size: 2-4 feet tall

Showy Milkweed (Asclepias speciosa)

- Light: Full sun

- Water: Average to dry, drought tolerant once established

- USDA Zone: 3-9

- Size: 2-4 feet tall, sometimes taller

White Milkweed (Asclepias variegata)

- Light: Part sun to part shade

- Water: Average to dry

- USDA Zone: 3-9

- Size: 1-4 feet tall

Whorled Milkweed (Asclepias verticillata)

- Light: Full sun

- Water: Average to dry, drought tolerant once established

- USDA Zone: 3-9

- Size: 2-3 feet tall

Green Milkweed (Asclepias viridis)

- Light: Full sun

- Water: Average

- USDA Zone: 5-9

- Size: 2-3 feet tall

Antelope Horns Milkweed (Asclepias asperula)

- Light: Full sun

- Water: Average

- USDA Zone: 7-9

- Size: 1-2 feet tall

A word of caution: It should be noted that the latex sap in milkweed can be very irritating to human skin for those who are sensitive or allergic to it. So, until you know if you are one of them, it’s wise to use gloves while handling the plants. If you’ve gotten the sap on your hands or gloves, be sure to keep them away from your eyes! If you do happen to get it in your eyes and experience burning, flush them immediately and thoroughly with water. If the burning persists, get medical care as soon as possible.

About the Author

Kylee Baumle is a citizen scientist who participates in several programs that provide data to researchers studying monarchs. A lifelong gardener and photographer with an endless curiosity about nature, Kylee is a regular columnist for both her local newspaper and Ohio Gardener magazine. She has also written for Horticulture, The American Gardener, Fine Gardening and Indiana Gardener. Her photography has appeared in Fine Gardening and in numerous books, magazines, garden industry trade publications and catalogs. In addition to The Monarch, she is co-author of Indoor Plant Décor. You can follow Kylee’s blog, Our Little Acre, where she writes about her love for the natural world.

While not the Monarch butterfly, I always have fennel and dill in the garden for butterflies. As my daughters were growing up, we would collect some of the caterpillars and ‘raise’ them and release them. My daughters learned early on the cycle of butterflies. Now it’s my grand daughter’s time. I love plants which encourage butterflies and birds to the garden.

I grew up on a farm where we got rid of it as fast as it appeared. Now I troll countryside ditches to get it for the monarchs.

What an informative post! I’ve been thinking about growing milkweed, for the sake of the butterflies and so my little daughter can learn about their life cycle. Thanks for the good info.

Thank you for such good information. I appreciate this as we are planning to put in a couple of butterfly garden areas in our condo complex.